Week 3: The Senate

Last week we covered how our votes are counted in the House of Representatives, with the party that wins a majority of the seats forming Government. Today, we’re going to be discussing the Senate. In particular, how the voting system differs and what that means.

What exactly is “The Senate”?

As mentioned in Module 1, Australia’s national Parliament is bicameral. This means it is divided into two houses, the House of Representatives (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). Parliament’s main job is to make laws. The Senate holds 76 seats, with Senators serving six-year terms. Federal elections are generally held every three years. This means at any given election, not all Senate seats will be up for grabs. For example, in 2019, 40 of the 76 Senate seats were up for election. The Senate is also known as the “House of Review”. It gets this name because its primary role is as a check on the Government’s power.

So, who are Senators?

Senators are elected to six-year terms. Every three years, half of the Senate spots are up for election. The only time all Senate spots are up for election is following a double dissolution election.

A double dissolution is a type of election that can be called by the Prime Minister when the Senate and House twice fail to agree on a piece of legislation. This occurred most recently in 2016. In a double dissolution, all HoR seats and Senate spots are up for grabs.

It’s worth remembering, Senators do not represent electorates. They actually represent their entire State or Territory. Each State has twelve Senators, each Territory has two.

What is proportional representation?

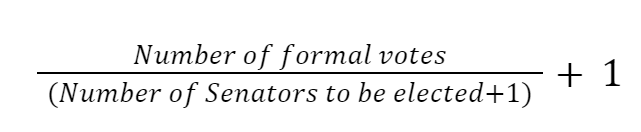

The Senate uses Proportional Representation. This means that candidates need to only secure a proportion of total first preference votes to be elected, compared to the HoR, where they must secure over 50 per cent of first preference votes. Here's how we calculate the proportion; it's really straightforward! Don’t tune out, it’s simple!

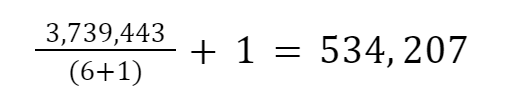

Using the Victorian example from the 2019 election:

In Victoria, 3,739,443 votes were submitted to determine six Senate vacancies. This meant that candidates needed to secure 534,207 first preference votes to get elected. Simple!

How preferences come into play

Once a candidate hits the quota in a Senate contest, their surplus preferences are then distributed amongst the remaining candidates. After the first round of preferences has been distributed, if vacancies remain, then the candidate with the least first preference votes is eliminated, and their preferences are distributed. The process continues until all vacancies are filled. It’s like the House of Reps, with some minor differences that are way too technical for this post, so don’t worry about them.

Why does Senate usually have more Independent and Minor party candidates?

Proportional Representation makes securing a Senate spot much easier than securing a seat in the House of Reps for minor parties and Independents. This is because candidates only need to gain a fraction of the total first preference votes (about 14 per cent when 6 spots are up for election) to land themselves in the Upper House. This explains why at the moment, 18 per cent of Senators do not belong to the major parties, compared to just 4.6 per cent in the House of Reps.

The intricacies of voting

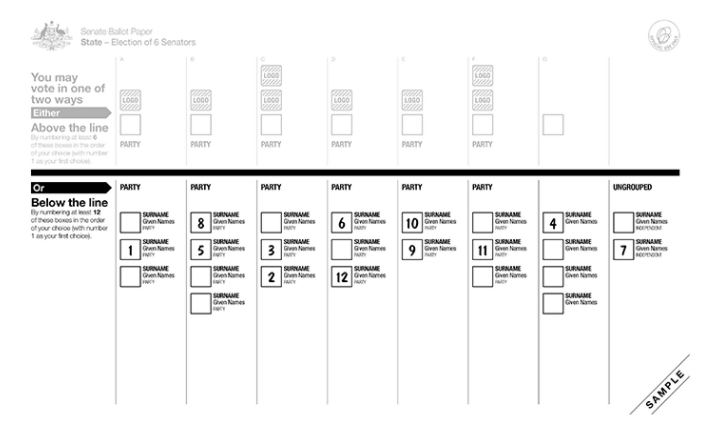

There’s two ways to vote: above the line or below the line.

Above the line, there is a single row of political parties to be ranked. The key here is that parties have their own preference deals, where they make agreements with other parties to share preferences. By voting above the line, you are letting the party of your choice allocate your preferences. For example, there may be five candidates from within Party A. By voting above the line, your preferences are then distributed according to Party A’s preferences, which are shown by the order they’ve listed candidates in the below-the-line section.

Voting below the line is the opposite, where the voter ranks individual candidates from at least 1-12 (but they rank them all if they choose, though few people opt for this form of self-inflicted torture). This allows the voter to exercise the most amount of influence on who gets elected to the Senate.